Schedule a Call

Ready to Upgrade Your Process Operations?

Explore how titanium alloys behave in additive manufacturing, from powder quality to heat treatment, helping engineers improve performance and certification.

Titanium additive manufacturing is no longer experimental. It is being considered for flight-critical and regulated components, and that is where teams start to feel friction. Powder variability, inconsistent heat treatment response, and gaps between printed and wrought material data create uncertainty long before a part reaches inspection.

For manufacturing engineers, this shows up as yield risk and unpredictable performance. For procurement and sourcing teams, it raises questions around supplier qualification, traceability, and certification readiness. Titanium itself is proven. The challenge is controlling the process and understanding how additive routes change alloy behavior.

This blog focuses on the metallurgical and process factors that actually determine success with titanium additive manufacturing. It covers powder quality, microstructural evolution, post-build heat treatment, and how these influence mechanical properties and compliance. Let’s get started.

Titanium additive manufacturing is gaining traction in aerospace and defense because it aligns with pressures the industry already faces. Fleet expansion, tighter fuel efficiency targets, and demand for complex, high-performance parts are accelerating the search for more flexible manufacturing routes.

Also Read: Aircraft Alloys: Properties, Types, and Aerospace Engineering Insights

Conventional forgings are supported by decades of production history, predictable microstructures, and well-established qualification pathways. Additive titanium follows a different metallurgical path. Layer-by-layer solidification introduces directionality, residual stress, and microstructural variation that do not appear in wrought or forged material.

Post-build heat treatment does not always translate directly from legacy titanium data and often requires requalification. While machinability can improve for complex geometries, consistency becomes driven by process control rather than material specification alone.

Primary risk vectors for engineering and procurement

These factors explain why titanium AM adoption is deliberate. The value is clear, but the risk must be engineered out early.

The bigger picture only holds if the basics are right. Powder quality is where it starts.

In titanium additive manufacturing, powder feedstock is not a commodity input. It is the starting point that defines microstructure, performance consistency, and certification risk downstream.

Key Powder Characteristics That Matter

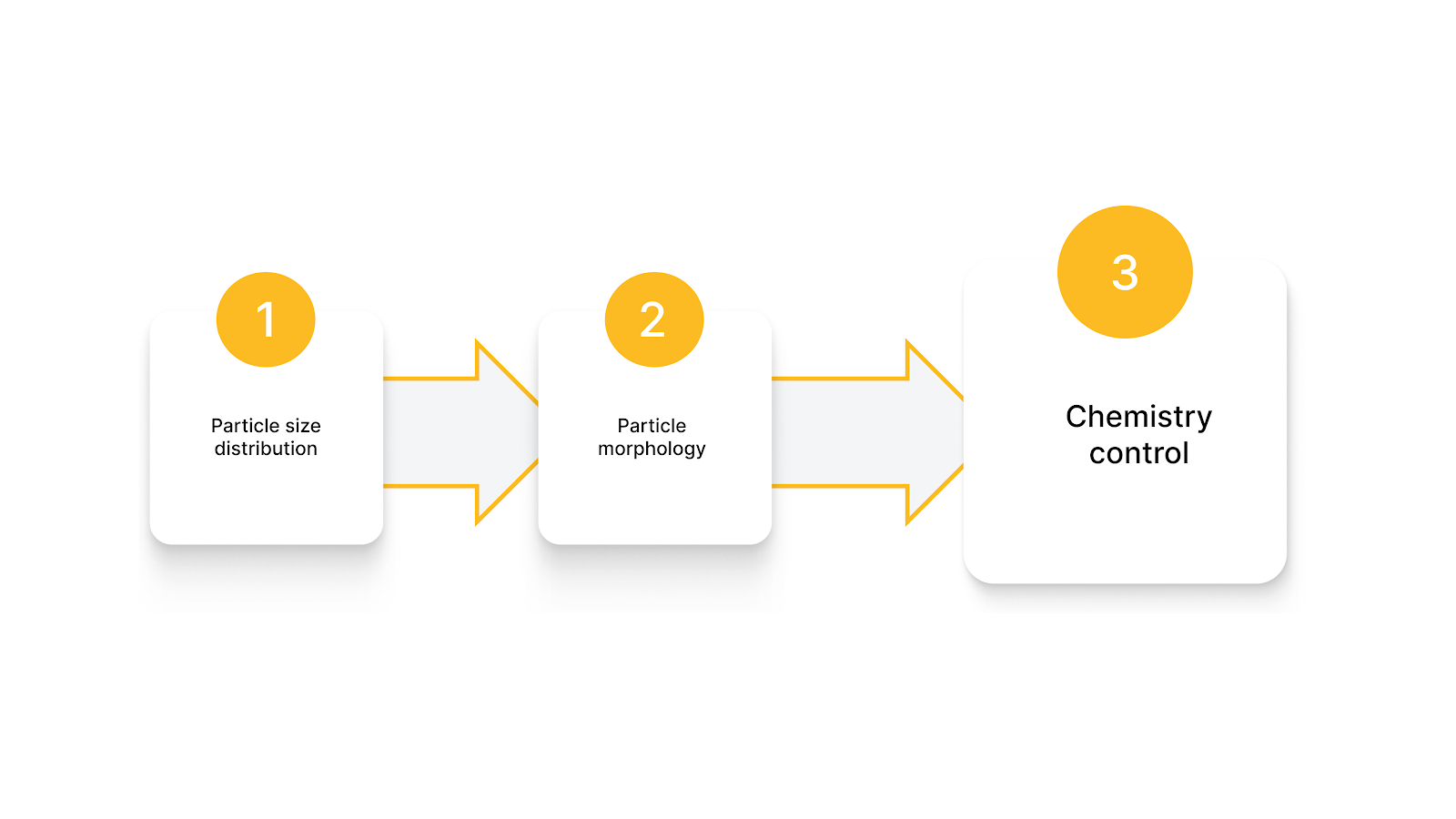

From a materials engineering standpoint, three attributes dominate outcomes:

Powder structure and particle size directly control thermal behavior during melting and solidification. Fine, uniform powders promote stable melt pools, consistent cooling, and finer prior-β grains with well-controlled α-phase formation. Broader or coarser distributions disrupt heat flow, leading to uneven cooling, columnar grain growth, and anisotropy.

As powder consistency drops, the process becomes more sensitive to laser power and scan speed. Parameter changes that should be benign begin to alter microstructure. In titanium additive manufacturing, microstructure is not defined by the machine alone. It is set first by the powder.

Next, let’s learn how titanium AM affects quality and certification.

Poor powder control rarely shows up immediately. It tends to surface later as internal porosity identified during NDT, wider scatter in tensile and fatigue results, and extended qualification cycles driven by inconsistent data.

In regulated aerospace programs, this quickly turns into a documentation burden. Powder traceability starts to matter as much as heat lot traceability does for wrought material, especially when audit questions arise months after production.

Typical risks engineers encounter include:

Effective control is procedural rather than corrective. Defined powder reuse limits, strict lot-level traceability, and controlled storage conditions reduce variability at the source. Just as important, powder suppliers must be qualified alongside the AM process itself.

In titanium additive manufacturing, powder quality sets the ceiling on achievable performance. Process control can refine outcomes, but it cannot recover from poor feedstock decisions made upstream.

For AMS 4911 6Al-4V titanium sheet and plate with full traceability and reliable lead times, Aero-Vac Alloys & Forge supports your requirements with certified material, specification control, and responsive technical support, so you can qualify with confidence.

Material quality is only part of the equation. The AM process matters just as much.

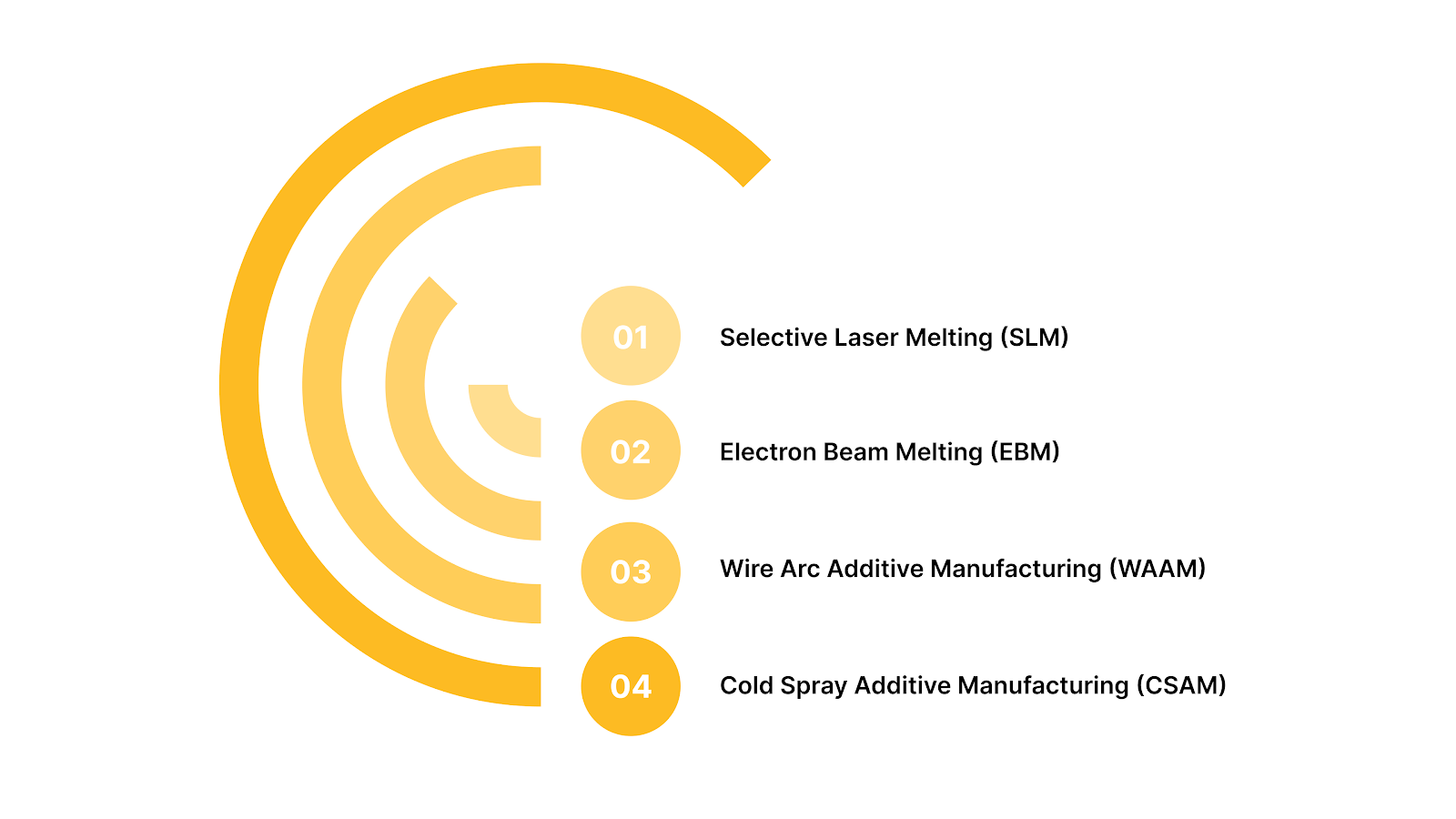

Selecting the right additive manufacturing process for titanium controls microstructure, mechanical performance, and certification risk. Each AM method imposes a distinct thermal and mechanical history on the alloy, which directly shapes how the material behaves in service and how difficult it will be to qualify.

SLM operates with very high energy density and rapid solidification. This creates steep thermal gradients and fast cooling rates, which strongly influence grain morphology and phase formation.

These conditions are responsible for the high strength often observed in as-built parts, but they also introduce residual stress and anisotropy that must be managed.

EBM maintains a preheated powder bed throughout the build. The slower cooling environment suppresses martensitic transformation and promotes more stable α/β microstructures. This typically results in improved ductility and more consistent mechanical behavior, simplifying downstream qualification.

WAAM introduces significantly more heat into the part over longer time scales. Repeated thermal cycling leads to coarse columnar β grains and layered microstructural variation through the build height. These effects are manageable but require careful control and, in many cases, post-processing.

Because CSAM avoids melting, it eliminates solidification-related defects and thermal distortion. However, titanium’s high strength makes particle bonding difficult, often resulting in porosity and inconsistent mechanical properties. Its role in mission-critical structures remains limited today.

Across all titanium additive manufacturing methods, a small set of parameters consistently determines outcomes. Energy input governs melt pool stability and phase formation, while scan speed and layer thickness directly control cooling rates and solidification time.

Thermal gradients influence residual stress accumulation and grain growth direction, and repeated thermal cycling affects phase stability as the build progresses in height.

Also Read: Bespoke Metal Fabrication: A Proven Guide for Aerospace & Defense Buyers

In titanium additive manufacturing, unique microstructures form as material is built layer by layer through rapid melting and solidification. These structures differ significantly from wrought or forged titanium and directly affect performance under load.

Compared to traditional wrought or forged titanium, AM builds can match or exceed static strength under controlled conditions, but they often require post-processing and careful monitoring to achieve consistent ductility and fatigue performance with low defect sensitivity.

As-built performance tells only part of the story. Structural reliability is established after the build is complete.

In aerospace and defense applications, titanium additive manufacturing does not end at the build stage. Post-processing is required to achieve stable, certifiable mechanical performance.

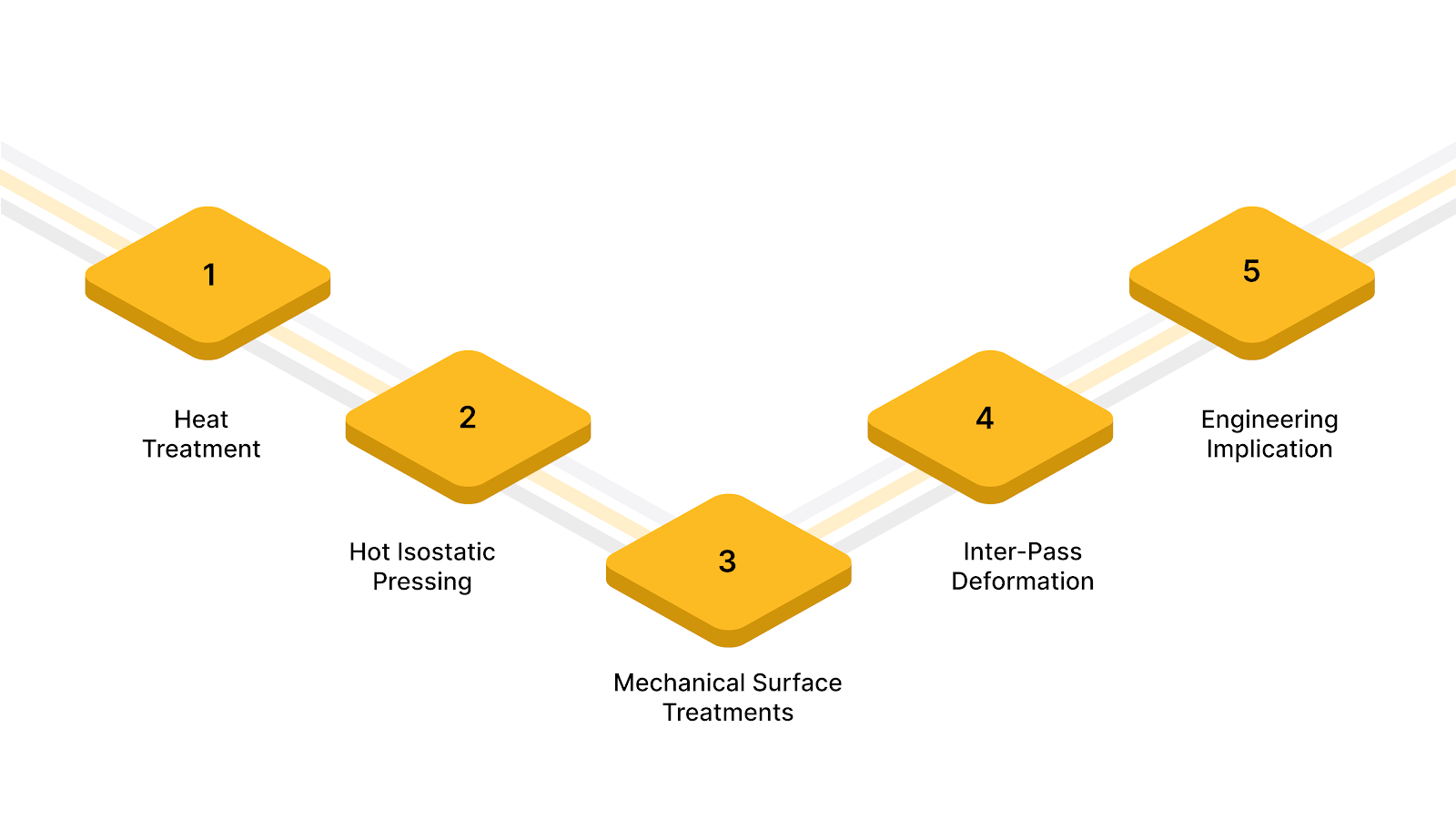

Post-build heat treatment is primarily used to transform non-equilibrium microstructures formed during rapid solidification. In powder-bed and wire-based processes, martensitic α′ phases are common. These phases increase strength but reduce ductility and fracture tolerance.

Controlled heat treatment decomposes α′ into α+β structures, improves ductility, and relieves residual stress. Tensile strength typically decreases as ductility improves. For most aerospace programs, this trade is acceptable and often necessary for certification.

Hot isostatic pressing combines high temperature and isostatic pressure to close internal voids and homogenize microstructure. Unlike heat treatment alone, HIP directly addresses internal defects.

This makes it a common requirement for fatigue-critical components. While HIP can slightly reduce peak strength, it consistently improves ductility and fatigue reliability, which matters more in service.

Processes such as shot peening introduce compressive residual stress at the surface, delaying crack initiation. This is particularly relevant for powder-bed processes where surface roughness is unavoidable. The effect is localized near the surface, so these treatments complement but do not replace HIP or heat treatment.

Directional grain growth creates anisotropic mechanical behavior in many AM titanium builds. Inter-pass deformation techniques, such as rolling between layers, refine grain structure and reduce anisotropy. These approaches are process-specific but can significantly improve property consistency.

For qualified titanium AM components, post-processing is not optional. Each step addresses a specific risk. Microstructural instability, porosity, residual stress, or anisotropy. Successful programs define these requirements early, before additive manufacturing becomes a downstream production constraint.

When titanium additive manufacturing is evaluated with this level of metallurgical and process discipline, it becomes a controllable production route rather than a qualification risk.

Once performance requirements are defined, material sourcing and processing support become the next control points.

Titanium additive manufacturing succeeds when material quality, processing control, and documentation stay aligned from the start. Aero-Vac supports that alignment with certified supply and first-step processing, which reduces downstream risk.

Where Aero-Vac adds value for titanium AM programs:

If your titanium AM program depends on traceable material, predictable lead times, and qualified processing support, Aero-Vac can support your next phase with confidence.

Titanium additive manufacturing offers compelling opportunities for aerospace and defense applications, but success depends on more than just printing a part. Alloy behavior, microstructure evolution, and post-processing outcomes ultimately determine whether titanium components meet mechanical, fatigue, and certification requirements.

Aero-Vac Alloys & Forge supports aerospace and defense teams with certified titanium alloys and processing expertise designed for qualification-ready additive manufacturing programs. Explore Aero-Vac’s certified titanium alloys, full traceability, and value-added services to support your qualification and production needs with confidence.

1. How does titanium additive manufacturing differ metallurgically from wrought or forged titanium?

Titanium AM creates non-equilibrium microstructures due to rapid solidification and thermal cycling. This often results in martensitic phases, anisotropy, and higher defect sensitivity compared to wrought or forged material.

2. Why is post-processing critical in titanium additive manufacturing?

As-built titanium AM parts typically contain porosity, residual stress, and unstable microstructures. Post-processing, such as heat treatment and HIP, is required to stabilize properties and meet fatigue and certification requirements.

3. How does porosity affect fatigue performance in titanium AM parts?

Even small internal pores act as fatigue crack initiation sites under cyclic loading. Without porosity reduction, fatigue life can be significantly lower and more variable than conventional titanium components.

4. Can titanium additive manufacturing meet aerospace certification requirements?

Yes, but only with controlled material input, documented process parameters, and validated post-processing. Qualification depends on repeatability, traceability, and performance consistency, not build success alone.

5. What role does material traceability play in titanium additive manufacturing programs?

Traceability links powder or feedstock chemistry, processing history, and inspection results. It is essential for audit readiness, root-cause analysis, and long-term program approval in regulated industries.